THE CHICKENS HAVE COME HOME TO ROOST

In the last 12 years, the management in the Department of Correction has been a dismal failure. Unfortunately, NYC Correction Officers and uniformed managers have been made the scapegoat, because now the chickens have come home to roost, and blame for failure must be placed on someone. Over the years, and as recently as Aug. 26, Bronx DA Darcel Clark warned the city and department that when crimes were committed behind bars,“theremust be administrative toolsfor swift and certain punishment” and “we cannot prosecute our way out of this.” The jails are out of control because theMayor, City Council and other lawmakers have systematically removed all accountability from incarcerated people behind bars.

The Bloomberg and de Blasio administrations removed uniformed managers from decision-making levels and appointed Commissioners with no experience running a jail system, and sometimes even a jail. During that time, Correction Officers and uniformed managers were rarely consulted when attempting to institute programs, policies, and procedures inside the city jails.

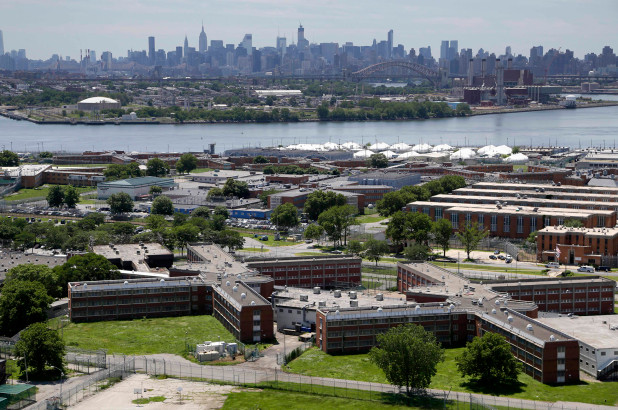

It’s been more than 12 years since DOC had a Commissioner take a stand against City Hall when its directives had adverse effects on the agency. From2009–2021, the city hasspent tens ofmillions of dollars on consultants, and the jails areworse than they’ve ever been. It is the belief among the rank and file that the last four Commissioners gave up control of RikersIsland in return for a blip on a resume.

The decision-making has been given to outside agencies and watchdog groups. We have had the Mayor, City Council, Board of Correction, consultants, Federal monitor and reform organizations produce bad choices, creating the current crisis. Correction Officers, staff, and inmates have been subjected to rules and policies that sound good in the world of algorithms and politics, but aren’t practical in operating a large jail system.

Correction Officers have seen new policies and procedures instituted by Commissioners who have absolutely no idea of

what cause and effectmeansin a jailsystemlike RikersIsland. To top it off, Correction Officers and uniformed managers have been forced to implement ideology disguised as rules and policies. There is a saying,“People don’t leave companies, they leave managers, and since 2009, the list of uniformed managers and line officers who left this agency is too long to list. The “Baby Boomer” generation that made up half of the uniformedworkforce has been retiring in large numbers, taking with themthe institutional knowledge of the DOCwhen it faced AIDS, H1N1, other communicable diseases, the crack epidemic, increasing incarcerations for “quality of life” crimes, and the explosion of gangsin the city. It faced these changes alongwith a rocky economy butsucceeded in not losing control of the jails.

Bottom Line: the next Mayor and Commissioner will have the daunting task of repairing a jail system neglected and mismanaged for the last 12 years.

ELIAS HUSAMUDEEN

Past President, Correction Officers’

Benevolent Association